India-Art

Jaipur, Jan 2014 Noted sculptor

K.S.Radhakrishnan has been spearheading a campaign to give legitimacy to open

air sculptures at public places in the last three decades. In 1986, one of Radhakrishnan’s

early public sculptures was installed in Bikaner. The artist re-connected with

the “venue” at the Jaipur Literature Festival - one of the largest free

literature gala in Asia – this week (Jan 18-21) to unveil a biographical

account of his art, “In the Open: The Sculptures of K.S. Radhakrishnan”

(published by Ojas Art). The volume chronicles the life and art of the sculptor

– his artistic journeys, inspirations, practices and contexts of his art.

Several of his sculptures were on display at the festival this week.

Born in Kottayam in

1956, Radhakrishnan went to Shantiniketan in 1993-1994 for formal training in

arts at the Kala Bhavan where he was inpsired by the idyllic locales and the lives of the ethnic communities around the university, Visva Bharti. It offered him space to express his response to the human struggle for survival and freedom to live life in synergy with natural environs.

“I have this intention

of making more open air sculptures. My teacher at Shantiniketan – Ramkinkar

Baij – made one of the earliest open air sculptures in 1936-1937. They were the

first breathing sculptures with life of their own,” Radhakrishnan said. The

artist, a native of Kerala but trained in the art movements of the Bengal school

at Shantiniketan combines Ramkinkar’s abstract figures with ethnic body

languages - belonging to the ancient races inhabiting remote regions of

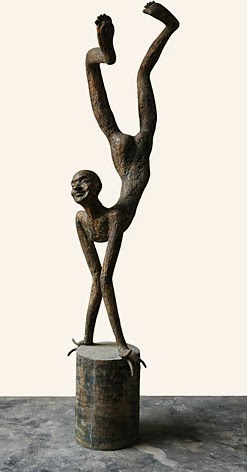

the country, including south India. His sculptures

seem to be suspended in space - flying and breathing at the same time.

“They are the

sculptures that start with clay. The movement takes on a kind of scale but at

the same time – the forms do not stay with you. They fly in open space to

escape the suffocation of confines. I suppose sculptures are to be seen,” he

said.

In India, “people don’t

see too many sculptures in public sphere because they are understood to be

monumental”. “A space is usually allocated for contemporary sculpture and to

start with, you need a public sponsorship. Open sculptures in public places are

still trying to find the right space,” Radhakrishnan said. Recalling a

commission for the New Delhi government, the sculptor said in 1996, “the Delhi government

had commissioned one of his sculptures for the garden of five senses.

“But it was not the

way an artist would approach the public space — I said it had to be my sculpture.

I managed to get what I wanted by donating the sculpture,” he said. Constrained resource and red tape often force

artists to limit their sphere of public engagements in art to mere showpieces —

sculptures which cost less money and are “visually attractive”. Art in public realm – open spaces— is yet to

open dialogue in the country on social issues linking society and communities

to aesthetic interventions and “raising awareness about causes ranging from

environment, gender, hygiene and even traffic”. Sculptures in public places

have been known to be defaced or vandalized across India — in mindless

backlashes over the efficacy “art” as spur for development in a nation of 1.2

billion where more than 40 per cent still subsist below poverty line with scant

appreciation for art.

However, author and

critic Johny ML tries to address this popular insularity to the solid arts observing

that “both the open air and public sculptures anticipate an audience that is

not strictly expected to be seen within an aesthetic context”. The viewer for a

public sculpture vary in character,

perspective, educational qualification, gender purpose and intention. The author points out the thin distinction

between open air sculptures and public sculptures. An open air sculpture can be

installed in the open — but at the same time they need not be necessarily

public sculpture. While a public sculpture may be in the open, it may also be

in a corporate museum.

The book which begins

with a general introduction to sculptures as being as the “exterior façade of

art” — applying to broader spectrums of artistic movements and landscapes, it brings

in Radhakrishnan’s art practice in the context of landscapes, his training at

Shantiniketan, influences and “practices”. It takes up specific sculptural forms

that he created as the beginning of his career as an artist — and studies their

progression and evolution as he tries to work on the same themes later in life.

One such motif is the “Musui”

— the head of a Santhali boy whom Radhakrishnan had met as a student in

Shantiniketan. “Musui was a bit autistic. One day after his modeling session,

Radhakrishnan gave him Rs 2. He took it happily and went away, when he came

back, Musui was transformed into a new personality. He had tonsured his head

and had shaved off his sparse beard and moustache. The blissful smile was

intact on his face,” Johny ML writes. Radhakrishnan

was riveted by Musui’s new appearance – and made fresh models, including a

bust.

When Radhakrishnan

decided to leave Shantiniketan for Delhi, he sawed off the head of the Musui

sculpture and carried it to Delhi — he kept it in his study. In the 1990s, he

decided to create another study of the character called Musui — an

icon for his sculptural progress. All his ensuing sculptures, the “Maiya”

series, “Conch Shells” and the “Woman with Violin”, the “Musui” makes its

imperceptible presence even as female protagonist. “Towards the end of 1990s,

we see Musui taking centrestage in Radhakrishnan’s sculptural outputs,” the

author said. The Musui continued to dominate his figurative terrain even when

the artist experimented with “combination figures and multiple human forms

within a single sculpture” later— compositions in which all the figures with many

arms, legs and torso in one frame seemed to be in flight at impossible angles

from a vertical perch or standing like flexible “reeds” in desolation .

K.S. Radhakrishnan understood

that the “interchanging nature of public sculptures and open air sculptures”.

For him, the polemic became a solution in itself when he started off with open

air sculptures — inspired by Ramkinkar Baij’s iconic “Santhal Family” at Visva Bharati

in Shantiniketan. He recognized the fact that a free standing sculpture negotiated

“both an idea and space within a solid form”.

The artist says “a

sculpture made of enduring material like marble, bronze, steel, granite should

be for public viewing rather than private viewing,” the artist observes in the

book. But as a sculptor in a country like India, where art is yet to become a sustainable

vocation, Radhakrishnan realizes the importance of patronage and the rationale

for “keeping sculptures within the confines of private collections”.

-Madhsuree Chatterjee

www.artsinfocus.webs.com

(a news portal for arts/literature/culture articles, news, views, features and essays)

No comments:

Post a Comment