South Asia –Books/Culture/Politics/Partition

By Madhusree

Chatterjee

New Delhi

Sixty seven

years after India was partitioned in 1947 for the first time to create Pakistan

and then again in 1971 to carve out Bangladesh, the voices narrating the

stories of the historic events are changing. The nostalgia has given away to detachment and

a dull ache – two characteristics that set the psyches of the second generation

of immigrants apart from the rest of the

native Indians. In place is wistfulness — a grief of not having been around,

missing out on what was so vital to life – the ancient blood roots that makes

the Indian sub-continent so distinctive culturally.

The formats

of Partition storytelling are morphing making way to new forms. The spirit of

Khushwant Singh’s flagship “Train of Pakistan” tales may still remain the powering

force of creativity, but the medium of storytelling has become more eclectic,

quixotic and rather adventurous. Pain tempers creative expressions

to spur experiments and brilliance in flashes.

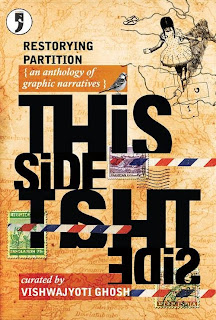

A new

anthology of Partition stories, “Restorying Partition: This Side, That Side (Yoda Press)” has used the graphic narrative –

the structure of animated story-telling – to capture 28 slices of memory by 48 writers

and graphic illustrators — spanning three

nations — India, Bangladesh and Pakistan — who live in three continents of US,

Europe and Asia. Curated by New Delhi-based

writer and animator Vishwajyoti Ghosh, the author of the graphic novel, “Delhi

Calm”, the Partition tales — short

graphic essays and memories — narrate events hinging around the two splits in the voices of the

second generation immigrants from south Asian perspectives. “This is a book, I

wanted to work on for a long time, much before I wrote my graphic novels, ‘Delhi

Calm’. I felt I was not equipped to

write about the Partition,”the curator said.

Vishwajyoti

Ghosh, a Delhiite, is one of the multitudes of Bengali settlers in New Delhi,

whose families are rooted in erstwhile East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. “These are the stories, I grew up with,” the

curator said. As a child in Lajpat Nagar — one of Delhi’s most steadfast

immigrant sprawl in the heart of the metropolis — and later in Chittaranjan

Park, a residential colony for displaced people from Bangladesh, Ghosh’s childhood narratives drew from the

notions of dislocations, angst, resettlement and rehabilitation.

In one of

the graphically illustrated stories, “A Good Education”, the curator returns to

a little space in Lajpat Nagar, “Kasturba Nagar”- a landscape of childhood.

The soul of

Kasturba Nagar, a refugee resettlement colony, was a home for widows and

children from Bangladesh, a mental asylum and staff quarters for government

officials. The inmates of the mental asylum

would often sneak into the widows’ home raising a hue and cry, Ghosh recalled.

It was a

multi-coloured demographic space with immigrants from Bangladesh and Pakistan cohabiting

in peaceful routine. The key to every

immigrant coming-of-age journey in Lajpat Nagar — like Ghosh’s grandparents — was

sending their children to good schools. Education was a passport to better life.

Lajpat Nagar

has not changed much in character. It remains a refugee cluster even to this

day. The erstwhile immigrants from Pakistan and Bangladesh are now landowners-

having built their own homes on the plots doled out by the government under the

refugee resettlement scheme. They have let their homes out to Afghan refugees

and to medical tourists. The business landscape

of immigrants - the market surrounding

Kasturba Nagar- has expanded to make

rooms for shops with sign boards in Dari and Pashtu.

“The

discourse of refugees is still running in Lajpat Nagar – as well as in the rest

of west Delhi,” Ghosh says.

In one of

the anecdotes, “Know Directions Home”, written and illustrated in the style of ethnic

Kutchhi embroidery from Gujarat, designer,

writer and filmmaker Nina Sabnani (from Mumbai) narrates a personalised tale of

a community from Adigram, a village along the Indo-Pakistan border, which was

forced to move to India after the partition in trucks.

The story grips the reader

with its element of suspense “when the trucks in which the immigrants were

travelling across the border suddenly retrace its route back to Pakistan under

the cover of darkness without the knowledge of the refugees”. The occupants refuse to go back to Adigram and threatens to

squat in the middle of nowhere till they are rehabilitated in India. An

exasperated local administration sends the villagers to Kutch – a barren and remote

tract without supplies.They build a

settlement in the arid salt pan – erecting small Bhunga huts made of chopped

wood, one of which slowly “turned into a school”.

The

narrative is redolent with resilience – the sheer courage of communities who defied

politics and geography to strike new roots- and survive. Eight years after the

fateful night of 1972, when the villagers landed in Kutch, the Indian

government declared them citizens. Creator

Sabnani, who teaches industrial design at IIT-Mumbai, has been working with

traditional threadwork of Gujarat – a legacy from across the border. Her movie,

“Tanko Bole Chhe (The Stitches Speak) “

has won several awards.

In “Water

Stories”, the trauma of partition haunts the protagonist – an immigrant from

erstwhile East Pakistan – to death in

the cursed river Padma, which is said to be “unrelenting in its anger and the

pain of Partition”. Years after the

Padma took the protagonist (a little

girl)’s mother before the family fled to Kolkata in India — and age felled her father in India, the young

woman returns to Bangladesh in cue of her father’s prophecy that “Padma had

cursed them” in search of the soul of the river. The “river with its tides of magical

lores and karmic connections” draws the woman in. “…And slowly she became the

river…They saw the large yellow moon rise in her dark dark eyes”.

The illustration

by Bangalore-based graphic artist and writer Appupen is kind of fairy-tale in rendition- long loopy

curves of mythological drawings that prise apart the dark magic trove of Padma.

A story by musician

Rabbi Shergill (of “Bulla ki Jaana” fame), “Cabaret Weimar”, celebrates 2047- one hundred years of partition. It is a metaphor

for the cabaret cultures on television and its spillover into our lives. “Thinking

is banned today, Revolution is but crap, Switch on the TV and Chill out like

1920s Berlin…” Shergill says.

Each tale is

different in flavor because they are widespread, poignant, sentimental and

funny- associated with millions of lives all of whom have a anecdote to narrate.

They come across as breathtaking largely for their stylized graphic art that touches

a gamut of practices, stylization, innovations, digitization and whips up sporadic

creative depths - in flashes.

“It was

tough. Some of the contributors were rookies. I had to handhold them all the way,” curator Ghosh told this writer.

He held two workshops – in Dhaka and Kolkata and worked with the Pakistani

writers on the Internet for the collection.

P.S. The

book was unveiled at Max Muller Bhavan- Goethe Instutut on Aug 30. Priced Rs

595

Great thoughts you got there, believe I may possibly try just some of it throughout my daily life.

ReplyDeleteBest Packers and Movers near Kasturba Nagar, Chennai